野蛮

野蛮(やばん)とは、文明?文化に対立する概念であり、文化の開けていない状態あるいは乱暴で礼節を知らないことを言う。未開や粗野と同義。しばしば自身を「文明」と称する人々によって相手に付けられるレッテルとして用いられる。野蛮だとされる民族は「蛮族」と呼ばれる。ここでは例として欧州人の蛮族観を説明する。

古代古典時代

古代ギリシアでは異国の民をバルバロイ(β?ρβαροι, Barbaroi)と呼んだ。歴史以前では必ずしも軽蔑のニュアンスはなかったようだが、ペルシア戦争で異国の侵入と破壊を経験したあたりから、ペルシアへの敵愾心、非ギリシア人への排外の感情とともに、英語のバーバリアン(Barbarian)という語にこめられるような蔑視のニュアンスを含む用法になったようである。

ギリシア人たちは自由なギリシア人に比べ、絶対的な王による専制下のバルバロイには奴隷の品性しかないと考えた。アリストテレスによれば「ギリシア人は捕らわれても自分自身を奴隷と呼ぶことを好まず、またバルバロイだけをそう呼ぼうとする」。古典古代のギリシア人にとって、自分以外に主人を持つものを奴隷とみなし、家の中での家長=主人と奴隷の関係を律する論理と、主人=家長である自由人同士との関係を律する論理は異なるものであった。従って、家の論理を拡張したものとしての王=家長=主人につかえるオリエントの臣民たちは奴隷に準じるものとして理解されたのであった。古代ローマ人にとっても、領外のガリア人、ゲルマン民族は蛮族にすぎなかった。ゲルマン民族がローマ領内に移動し、キリスト教による平等主義で教化されたヨーロッパ世界でもこの構図は、形を変えて繰りかえされる。

A barbarian is

a human who

is perceived to be uncivilised or primitive.

The designation is usually applied as generalization based

on a popular stereotype;

barbarians can be any member of a nation judged

by some to be less civilised or orderly (such as

a tribal society),

but may also be part of a certain

"primitive" cultural

group (such as nomads)

or social

class (such as bandits)

both within and outside one's own nation. Alternatively, they may

instead be admired and romanticised as noble savages. In

idiomatic or figurative usage, a "barbarian" may also be an

individual reference to a brutal, cruel, warlike, insensitive

person.[1]

The term originates from the Greek: β?ρβαρο? (barbaros).

In ancient times,

the Greeks used

it mostly for people of different cultures, but there are examples

where one Greek city or state would use the word to attack another.

In the early modern

period and sometimes later, Greeks used it for

the Turks, in a

clearly pejorative way.[2][3] Comparable

notions are found in non-European civilizations,

notably China and Japan. During

the Roman Empire, the

Romans used the word "barbarian" for many people, such as

the Germanics, Celts, Gauls, Iberians, Thracians, Parthians and Sarmatians.

Etymology

The Ancient

Greek word β?ρβαρο? (barbaros),

"barbarian", was an antonym for πολ?τη? (polits),

"citizen" (from π?λι? – polis, "city-state").

The earliest attested form of the word is

the Mycenaean

Greek ???, pa-pa-ro, written

in Linear

B syllabic script.[4][5]

The Greeks used the term barbarian for all

non-Greek-speaking peoples, including

the Egyptians, Persians, Medes and Phoenicians,

emphasisising their otherness. However, in various occasions, the

term was also used by Greeks, especially

the Athenians, to deride

other Greek tribes and states (such as Epirotes, Eleans, Macedonians, Boeotians and Aeolic-speakers)

but also fellow Athenians, in a pejorative and politically

motivated manner.[6][7][8][9] Of

course, the term also carried a cultural dimension to its dual

meaning.[10][11]The

verb βαρβαρ?ζω (barbaríz) in ancient

Greek meant to behave or talk like a

barbarian, or to hold with the barbarians.[12]

Plato (Statesman 262de)

rejected the Greek–barbarian dichotomy as a logical absurdity on

just such grounds: dividing the world into Greeks and non-Greeks

told one nothing about the second group, yet Plato used the term

barbarian frequently in his seventh letter.[13] In Homer's works, the

term appeared only once (Iliad 2.867),

in the form βαρβαρ?φωνο? (barbarophonos) ("of

incomprehensible speech"), used of the Carians fighting

for Troy during

the Trojan War. In

general, the concept of barbaros did not figure

largely in archaic literature before the 5th

century BC.[14] Still

it has been suggested that "barbarophonoi" in

the Iliadsignifies not those who spoke a

non-Greek language but simply those who spoke Greek

badly.[15]

A change occurred in the connotations of the word after the

Greco-Persian Wars in the first half of the 5th century BC. Here a

hasty coalition of Greeks defeated the

vast Persian

Empire. Indeed, in the Greek of this period 'barbarian' is

often used expressly to refer to Persians, who were enemies of the

Greeks in this war.[16]

The Romans used the term barbarus for

uncivilised people, opposite to Greek or Roman, and in fact, it

became a common term to refer to all foreigners among Romans after

Augustus age (as, among the Greeks, after the Persian wars, the

Persians), including the Germanic peoples, Persians, Cauls,

Phoenicians and Carthaginians.[17]

The Greek term barbaros was the

etymological source for many words meaning "barbarian", including

English barbarian, which was first recorded in

16th century Middle

English.

A word barbara- is also found

in the Sanskrit of

ancient India.[18][19][20][21] The

Greek word barbaros is related to

Sanskrit barbaras (stammering).[22]

Semantics

The Oxford

English Dictionary defines five meanings

of the noun barbarian, including an

obsolete Barbaryusage.

- 1. etymologically, A foreigner, one whose

language and customs differ from the speaker's.

- 2. Hist. a. One not a

Greek. b. One living outside

the pale of the Roman empire and its civilization, applied

especially to the northern nations that overthrew

them. c. One outside the pale

of Christian

civilization. d. With the Italians of

the Renascence: One of a nation outside of Italy.

- 3. A rude, wild,

uncivilized person. b. Sometimes

distinguished from savage (perh. with a

glance at 2). c.Applied by the Chinese contemptuously

to foreigners.

- 4. An uncultured

person, or one who has no sympathy with literary culture.

- ?5. A native of Barbary.

[See Barbary

Coast.] Obs. ?b. Barbary

pirates & A

Barbary horse. Obs.[23]

The OED barbarous entry

summarizes the semantic history. "The sense-development in ancient

times was (with the Greeks) 'foreign, non-Hellenic,' later

'outlandish, rude, brutal'; (with the Romans) 'not Latin nor

Greek,' then 'pertaining to those outside the Roman empire'; hence

'uncivilized, uncultured,' and later 'non-Christian,' whence

'Saracen, heathen'; and generally 'savage, rude, savagely cruel,

inhuman.'"

"Barbarian" in Greek

historical contexts

Slavery in Greece

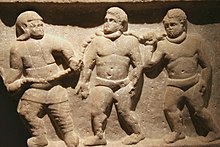

![蛮族 - 何新博客管理员 - 何新网易博客]()

Slaves in chains, relief found at Smyrna (present

day

?zmir,

Turkey), 200

AD

A parallel factor was the growth of chattel

slavery especially

in Athens. Although

enslavement of Greeks for non-payment of debt continued

in most Greek states, it was banned in Athens

under Solon in

the early 6th century BC. Under

the Athenian

democracy established ca. 508

BC slavery came

to be used on a scale never before seen among the Greeks. Massive

concentrations of slaves were worked under especially brutal

conditions in the silver mines at Laureion—a major vein

of silver-bearing ore was found there in 483 BC—while the

phenomenon of skilled slave craftsmen producing manufactured goods

in small factories and workshops became increasingly common.

Furthermore, slaves were no longer the preserve of the rich: all

but the poorest of Athenian households came to have slaves to

supplement the work of their free members. Overwhelmingly, the

slaves of Athens were "barbarian" in origin[citation needed],

drawn especially from lands around the Black

Sea such as Thrace and Taurica (Crimea), while

from Asia

Minor came above

all Lydians, Phrygians and Carians. Aristotle (Politics1.2–7;

3.14) even states that barbarians are slaves by nature.

From this period, words like barbarophonos, cited above from Homer,

began to be used not only of the sound of a foreign language but of

foreigners speaking Greek improperly. In Greek, the notions of

language and reason are easily confused in the

word logos,

so speaking poorly was easily conflated with being stupid.

Further changes occurred in the connotations

of barbari/barbaroi in Late

Antiquity,[24] when

bishops and catholikoi were

appointed to sees connected to cities among the

"civilized" gentes

barbaricae such as

in Armenia or Persia, whereas

bishops were appointed to supervise entire peoples among the less

settled.

Eventually the term found a hidden meaning

by Christian Romans through

the folk

etymology of Cassiodorus. He

stated the word barbarian was "made up

of barba (beard)

and rus (flat land); for

barbarians did not live in cities, making their abodes in the

fields like wild animals".[25]

The female given name "Barbara"

originally meant "a barbarian woman", and as such was likely to

have had a pejorative meaning—given that most such women in

Graeco-Roman society were of a low social status (often being

slaves).[citation

needed][dubious – discuss] However, Saint

Barbara is mentioned as being the daughter of

rich and respectable Roman citizens. Evidently, by her time (about

300 CE according

to Christian hagiography, though

some historians put the story much later) the name no longer had

any specific ethnic or pejorative connotations. This conclusion is,

however, questionable, as many authorities think it possible that

her story is fictitious, including the Roman Catholic Church since

1969 (for details of these doubts, see

under Saint

Barbara, Veneration).

Hellenic stereotypes

Out of those sources the Hellenic stereotype was elaborated:

barbarians are like children, unable to speak or reason properly,

cowardly, effeminate, luxurious, cruel, unable to control their

appetites and desires, politically unable to govern themselves.

These stereotypes were voiced with much shrillness by writers

like Isocrates in

the 4th century BCE who

called for a war of conquest against Persia as

a panacea for

Greek problems.

However, the Hellenic stereotype of barbarians was not a universal

feature of Hellenic culture. Xenophon, for

example, wrote the Cyropaedia, a

laudatory fictionalised account of Cyrus the

Great, the founder of the Persian empire, effectively

a utopian text.

In his Anabasis,

Xenophon's accounts of the Persians and other non-Greeks he knew or

encountered hardly seem to be under the sway of these stereotypes

at all.

The renowned orator Demosthenes made

derogatory comments in his speeches, using the word

"barbarian."

Barbarian is

used in its Hellenic sense by St.

Paul in the New

Testament (Romans 1:14)

to describe non-Greeks, and to describe one who merely speaks a

different language (1

Corinthians 14:11).

About a hundred years after Paul's time, Lucian –

a native of Samosata, in the

former kingdom of Commagene, which had

been absorbed by the Roman

Empire and made part of the province

of Syria –

used the term "barbarian" to describe himself. As he was a noted

satirist, this could have been a deprecating self-irony. It might

also have indicated that he was descended from Samosata's original

Semitic population – likely to have been called "barbarians" by

later Hellenistic, Greek-speaking settlers, and who might have

eventually taken up this appellation themselves.[26][27]

The term retained its standard usage in

the Greek

language throughout the Middle Ages, as it was

widely used by the Byzantine

Greeks until the fall of

the Byzantine

Empire in the 15th century.

Cicero described

the mountain area of inner Sardinia as

"a land of barbarians," with these inhabitants also known by the

manifestly pejorative term latrones

mastrucati ("thieves with a rough garment in

wool"). The region is up to the present known as "Barbagia"

(in Sardinian Barbàgia or Barbàza),

which is traceable to this old "barbarian" designation – but no

longer consciously associated with it, and used naturally as the

name of the region by its own inhabitants.

The Dying Galatian

statue

Some insight about the Hellenistic perception of and attitude to

"Barbarians" can be taken from the "Dying Galatian",

a statue commissioned by Attalus

I of Pergamon to

celebrate his victory over the Celtic Galatiansin Anatolia (the

bronze original is lost, but a Roman marble copy

was found in the 17th century).[28] The

statue depicts with remarkable realism a dying Celt warrior with a

typically Celtic hairstyle and moustache. He lies on his fallen

shield while sword and other objects lie beside him. He appears to

be fighting against death, refusing to accept his fate.

The statue serves both as a reminder of the Celts' defeat, thus

demonstrating the might of the people who defeated them, and a

memorial to their bravery as worthy adversaries. The message

conveyed by the sculpture, as H.

W. Janson comments, is that "they knew how to

die, barbarians that they were."[29]

The Greeks admired Scythians and Galatians as

heroic individuals – even in the case of Anacharsis as

philosophers – but considered their culture to be barbaric.

The Romans indiscriminately

regarded the various Germanic

tribes, the settled Gauls, and the

raiding Huns as

barbarians.

The Romans adapted the term to refer to anything non-Roman. The

German cultural historian Silvio Vietta points out that the meaning

of the word "barbarous" has undergone a semantic change in modern

times, after Michel de

Montaigne used it to characterize the

activities in the New World of the Spaniards – supposedly

representatives of the "higher" European culture – as "barbarous,"

in a satirical essay of the year 1580.[30] It

was not the supposedly "uncivilized" Indian tribes who were

"barbarous," but the conquering Spaniards. Montaigne argued that

Europeans noted the barbarism of other cultures but not the crueler

and more brutal actions of their own society, particularly (in his

time) in the so-called religious wars. Montaigne's people – the

Europeans – were the real "barbarians." In this way, the

Eurocentric argument was turned around and applied against the

European invaders. With this shift of meaning a whole literature

arose in Europe that characterized the indigenous Indian peoples as

innocent, and the militarily superior Europeans as "barbarous"

intruders into a paradisiacal world.[31][32]

"Barbarian" in

international historical contexts

Historically, the term barbarian has seen

widespread use, in English. Many peoples have dismissed alien

cultures and even rival civilizations, because they were

unrecognizably strange. For instance, the

nomadic steppe

peoples north of

the Black Sea, including

the Pechenegs and

the Kipchaks, were called

barbarians by Byzantines.[33]

Berber and North African

cultures

![蛮族 - 何新博客管理员 - 何新网易博客]()

Ransom of Christian slaves held in Barbary, 17th century

The Berbers of North

Africa were among the many peoples called

"Barbarian" by the Romans; in their case, the name remained in use,

having been adopted by the Arabs (see Berber

etymology) and is still in use as the name for the non-Arabs in

North Africa (though not by themselves). The geographical

term Barbary or Barbary

Coast, and the name of the Barbary

pirates based on that coast (and who were not

necessarily Berbers) were also derived from it.

The term has also been used to refer to people

from Barbary, a region

encompassing most of North Africa. The

name of the region, Barbary, comes from the

Arabic word Barbar, possibly from

the Latin word barbaricum, meaning

"land of the barbarians."

Many languages define the "Other" as those who do not speak one's

language; Greek barbaroi was paralleled

by Arabic ajam "non-Arabic

speakers; non-Arabs; (especially) Persians."[34]

Hindu culture

In the ancient Indian epic Mahabharata,

the Sanskrit word barbara- meant

"stammering, wretch, foreigner, sinful people, low and

barbarous".[35]

Indic peoples anciently referred to foreigners

as Mleccha "dirty

ones; barbarians."[36][37] Indic

peoples of the Vedic

period used mleccha much as the

ancient Greeks used barbaros, "originally to indicate the

uncouth and incomprehensible speech of foreigners and then extended

to their unfamiliar behavior."[38] In

the ancient texts, Mlecchas are people who

are dirty and who have given up the Vedic beliefs.

Today this term implies those with bad hygiene.[39][40] Among

the tribes termed Mleccha were Sakas, Huna

people, Yonas, Kambojas, the Pahlavas,

Kiratas, Khasas, Bahlika

people and Rishikas.[39]

Chinese culture

The term "Barbarian" in traditional Chinese culture had a few

interesting aspects. For one thing, Chinese has more than one

historical "barbarian" exonym.

Several historical Chinese

characters for non-Chinese peoples

were graphic

pejoratives, the character for the Yao

people, for instance, was changed

from yao 猺 "jackal"

to yao 瑤 "precious jade"

in the modern period.[41] The

original Hua–Yi

distinction between "Chinese" and "barbarian"

was based on culture and power but not on race.

Historically, the Chinese used various words for foreign ethnic

groups. They include terms like 夷 Yi, which is often translated as

"barbarians." Despite this conventional translation, there are also

other ways of translating Yi into English. Some

of the examples include "foreigners,"[42] "ordinary

others,"[43] "wild

tribes,"[44] "uncivilized

tribes,"[45] and

so forth.

History and

terminology

Chinese historical records mention what may now perhaps be termed

"barbarian" peoples for over four millennia, although this

considerably predates the Greek

language origin of the term "barbarian", at

least as is known from the thirty-four centuries of written records

in the Greek language. The sinologist Herrlee

Glessner Creel said, "Throughout Chinese

history "the barbarians" have been a constant motif, sometimes

minor, sometimes very major indeed. They figure prominently in the

Shang oracle inscriptions, and the dynasty that came to an end only

in 1912 was, from the Chinese point of view, barbarian."[46]

Shang

dynasty (1600–1046 BC) oracles and bronze

inscriptions first recorded specific

Chinese exonyms for

foreigners, often in contexts of warfare or tribute.

King Wu

Ding (r. 1250–1192 BC), for instance, fought

with the Guifang 鬼方, Di 氐,

and Qiang 羌

"barbarians."

During the Spring and

Autumn period (771–476 BC), the meanings of

four exonyms were expanded. "These included Rong, Yi, Man, and

Di—all general designations referring to the barbarian

tribes."[47] These Siyi 四夷

"Four Barbarians", most "probably the names of ethnic groups

originally,"[48]were

the Yi or Dongyi 東夷

"eastern barbarians," Man or Nanman 南蠻

"southern barbarians," Rong or Xirong 西戎

"western barbarians," and Di or Beidi 北狄

"northern barbarians." The Russian

anthropologist Mikhail

Kryukov concluded.

Evidently, the barbarian tribes at first had individual names, but

during about the middle of the first millennium B.C., they were

classified schematically according to the four cardinal points of

the compass. This would, in the final analysis, mean that once

again territory had become the primary criterion of the we-group,

whereas the consciousness of common origin remained secondary. What

continued to be important were the factors of language, the

acceptance of certain forms of material culture, the adherence to

certain rituals, and, above all, the economy and the way of life.

Agriculture was the only appropriate way of life for

the Hua-Hsia.[49]

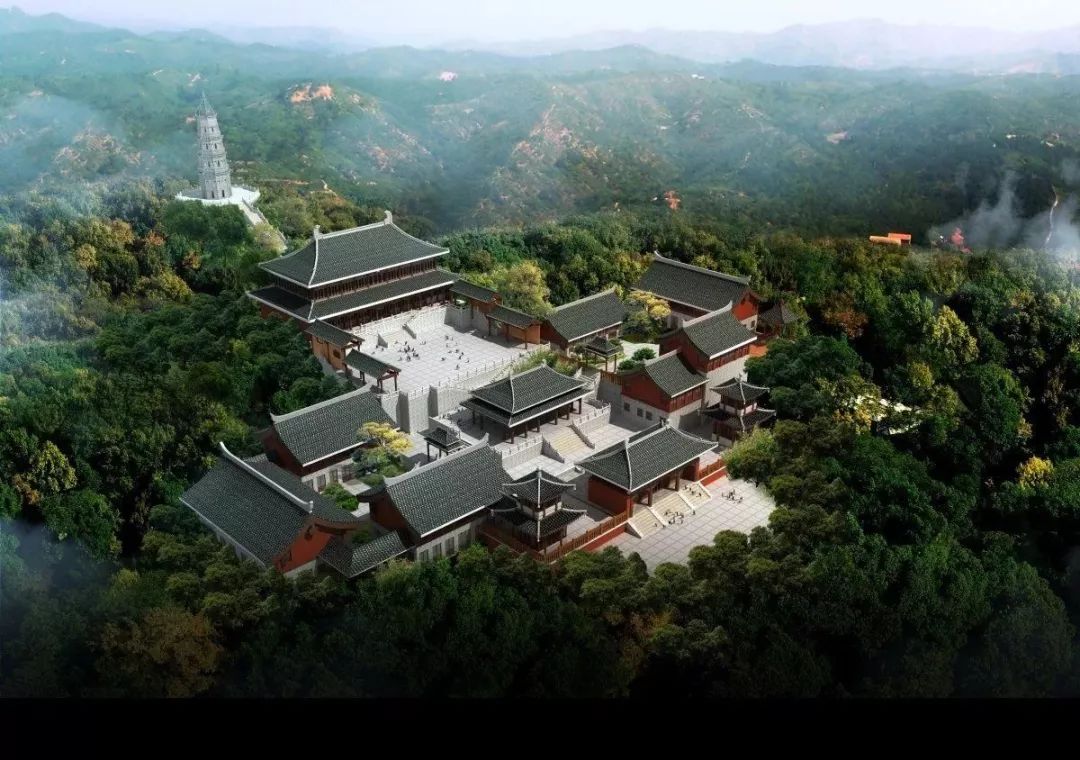

![蛮族 - 何新博客管理员 - 何新网易博客]()

A scene of the Chinese campaign against

the

Miao in

Hunan, 1795

The Chinese

classics use compounds of these four generic

names in localized "barbarian tribes" exonyms such as "west and

north" Rongdi,

"south and east" Manyi, Nanyibeidi "barbarian

tribes in the south and the north," and Manyirongdi "all kinds

of barbarians." Creel says the Chinese evidently came to

use Rongdi and Manyi "as

generalized terms denoting 'non-Chinese,' 'foreigners,'

'barbarians'," and a statement such as "the Rong and Di are wolves"

(Zuozhuan, Min 1) is "very much

like the assertion that many people in many lands will make today,

that 'no foreigner can be trusted'."

The Chinese had at least two reasons for vilifying and depreciating

the non-Chinese groups. On the one hand, many of them harassed and

pillaged the Chinese, which gave them a genuine grievance. On the

other, it is quite clear that the Chinese were increasingly

encroaching upon the territory of these peoples, getting the better

of them by trickery, and putting many of them under subjection. By

vilifying them and depicting them as somewhat less than human, the

Chinese could justify their conduct and still any qualms of

conscience.[50]

This word Yi has both specific

references, such as to Huaiyi 淮夷 peoples in

the Huai

River region, and generalized references to

"barbarian; foreigner; non-Chinese." Lin Yutang's

Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern

Usage translates Yi as "Anc[ient]

barbarian tribe on east border, any border or foreign

tribe."[51] The

sinologist Edwin G.

Pulleyblank says the

name Yi "furnished the

primary Chinese term for 'barbarian'," but "Paradoxically the Yi

were considered the most civilized of the non-Chinese

peoples.[52]

Idealization

A few contexts in the Chinese classics romanticize or idealize

barbarians, comparable to the western noble

savage construct. For instance, the

Confucian Analects records:

- The Master

said, The [夷狄] barbarians of the East and North have retained their

princes. They are not in such a state of decay as we in China.

- The Master

said, The Way makes no progress. I shall get upon a raft and float

out to sea.

- The Master

wanted to settle among the [九夷] Nine Wild Tribes of the East.

Someone said, I am afraid you would find it hard to put up with

their lack of refinement. The Master said, Were a true gentleman to

settle among them there would soon be no trouble about lack of

refinement.[53]

The translator Arthur

Waley noted that, "A certain idealization of

the 'noble savage' is to be found fairly often in early Chinese

literature", citing the Zuo

Zhuan maxim, "When the Emperor no longer

functions, learning must be sought among the 'Four Barbarians,'

north, west, east, and south."[54]Professor

Creel said,

From ancient to modern times the Chinese attitude toward people not

Chinese in culture—"barbarians"—has commonly been one of contempt,

sometimes tinged with fear ... It must be noted

that, while the Chinese have disparaged barbarians, they have been

singularly hospitable both to individuals and to groups that have

adopted Chinese culture. And at times they seem to have had a

certain admiration, perhaps unwilling, for the rude force of these

peoples or simpler customs.[55]

In a somewhat related example, Mencius believed

that Confucian practices were universal and timeless, and thus

followed by both Hua and Yi, "Shunwas

an Eastern barbarian; he was born in Chu Feng, moved to Fu Hsia,

and died in Ming T'iao. King

Wen was a Western barbarian; he was born in

Ch'i Chou and died in Pi Ying. Their native places were over a

thousand li apart, and there

were a thousand years between them. Yet when they had their way in

the Central Kingdoms, their actions matched like the two halves of

a tally. The standards of the two sages, one earlier and one later,

were identical."[56]

The prominent Shuowen

Jiezi character dictionary (121 CE), which

defines yi 夷 as 平 "level;

peaceful" or 東方之人 "people of eastern regions," first records that

this Han

Dynasty (206 BCE–220

CE) regular

script 夷 and the Qin

Dynasty (221–207

BCE) seal

script for shi incorporate both

the 大 "big" and 弓 "bow" radicals.

According to the Shuowen, the radical “big” in the

character yi means "person".

Pejorative Chinese

characters

Some Chinese

characters used to transcribe non-Chinese

peoples were graphically pejorative ethnic slurs,

where the insult derived not from the Chinese word but from the

character used to write it. Take for instance,

the Written

Chinese transcription

of Yao "the Yao people",

who primarily live in the mountains of southwest China and Vietnam.

When 11th-century Song

Dynasty authors first transcribed

the exonym Yao,

they insultingly chose yao 猺 "jackal" from a

lexical selection of over 100 characters

pronounced yao (e.g., 腰 "waist", 遙

"distant", 搖 "shake"). During a series of 20th-century

Chinese language

reforms, this graphic pejorative 猺 (written

with the 犭"dog/beast radical")

"jackal; the Yao" was replaced twice; first with the invented

character yao 傜 (亻"human radical")

"the Yao", then with yao 瑤 (玉

"jade radical")

"precious jade; the Yao." Chinese orthography (symbols

used to write a language) can provide unique opportunities to write

ethnic insults logographically that

do not exist alphabetically. For the Yao ethnic group, there is a

difference between the transcriptions Yao 猺 "jackal"

and Yao 瑤 "jade" but none

between the romanizations Yao and Yau.[57]

Cultural and racial

barbarianism

![蛮族 - 何新博客管理员 - 何新网易博客]()

The purpose of the

Great Wall

of China was to stop the "barbarians" from

crossing the northern border of China.

According to the archeologist William Meacham, it was only by the

time of the late Shang

dynasty that one can speak of "Chinese,"

"Chinese

culture," or "Chinese civilization." "There is a sense in which

the traditional view of ancient Chinese history is correct (and

perhaps it originated ultimately in the first appearance of

dynastic civilization): those on the fringes and outside this

esoteric event were "barbarians" in that they did not enjoy (or

suffer from) the fruit of civilization until they were brought into

close contact with it by an imperial expansion of the civilization

itself."[58] In

a similar vein, Creel explained the significance of

Confucian li "ritual;

rites; propriety".

The fundamental criterion of "Chinese-ness," anciently and

throughout history, has been cultural. The Chinese have had a

particular way of life, a particular complex of usages, sometimes

characterized as li. Groups that conformed to this way of

life were, generally speaking, considered Chinese. Those that

turned away from it were considered to cease to be

Chinese. ... It was the process of acculturation,

transforming barbarians into Chinese, that created the great bulk

of the Chinese people. The barbarians of Western Chou times were,

for the most part, future Chinese, or the ancestors of future

Chinese. This is a fact of great importance. ...

It is significant, however, that we almost never find any

references in the early literature to physical differences between

Chinese and barbarians. Insofar as we can tell, the distinction was

purely cultural.[48]

Dik?tter says,

Thought in ancient China was oriented towards the world,

or tianxia, "all under

heaven." The world was perceived as one homogenous unity named

"great community" (datong) The

Middle Kingdom [China], dominated by the assumption of its cultural

superiority, measured outgroups according to a yardstick by which

those who did not follow the "Chinese ways" were considered

"barbarians." A Theory of "using the Chinese ways to transform the

barbarian" as strongly advocated. It was believed that the

barbarian could be culturally assimilated. In the Age of Great

Peace, the barbarians would flow in and be transformed: the world

would be one.[59]

According to the Pakistani academic M. Shahid Alam,

"The centrality of culture, rather than race, in the Chinese world

view had an important corollary. Nearly always, this translated

into a civilizing mission rooted in the premise that 'the

barbarians could be culturally assimilated'";

namely laihua 來化 "come and be

transformed" or Hanhua 漢化 "become

Chinese; be sinicized."[60]

Two millennia before the French

anthropologist Claude

Lévi-Strauss wrote The Raw and

the Cooked, the Chinese differentiated "raw" and "cooked"

categories of barbarian peoples who lived in China.

The shufan 熟番 "cooked [food

eating] barbarians" are sometimes interpreted as Sinicized, and

the shengfan 生番 "raw [food

eating] barbarians" as not Sinicized.[61] The Liji gives

this description.

The people of those five regions – the Middle states, and the

[Rong], [Yi] (and other wild tribes around them) – had all their

several natures, which they could not be made to alter. The tribes

on the east were called [Yi]. They had their hair unbound, and

tattooed their bodies. Some of them ate their food without its

being cooked with fire. Those on the south were called Man. They

tattooed their foreheads, and had their feet turned toward each

other. Some of them ate their food without its being cooked with

fire. Those on the west were called [Rong]. They had their hair

unbound, and wore skins. Some of them did not eat grain-food. Those

on the north were called [Di]. They wore skins of animals and

birds, and dwelt in caves. Some of them did not eat

grain-food.[62]

Dik?tter explains the close association

between nature and

nurture. "The shengfan, literally 'raw barbarians',

were considered savage and resisting.

The shufan, or

'cooked barbarians', were tame and submissive. The consumption of

raw food was regarded as an infallible sign of savagery that

affected the physiological state of the barbarian."[63]

Some Warring

States period texts record a belief that the

respective natures of the Chinese and the barbarian were

incompatible. Mencius, for instance, once stated: "I have heard of

the Chinese converting barbarians to their ways, but not of their

being converted to barbarian ways."[64]Dik?tter

says, "The nature of the Chinese was regarded as impermeable to the

evil influences of the barbarian; no retrogression was possible.

Only the barbarian might eventually change by adopting Chinese

ways."[65]

However, different thinkers and texts convey different opinions on

this issue. The prominent Tang Confucian Han Yu, for example, wrote

in his essay Yuan

Dao the following: "When Confucius wrote

the Chunqiu,

he said that if the feudal lords use Yi ritual, then they should be

called Yi; If they use Chinese rituals, then they should be called

Chinese." Han Yu went on to lament in the same essay that the

Chinese of his time might all become Yi because the Tang court

wanted to put Yi laws above the teachings of the former

kings.[66] Therefore,

Han Yu's essay shows the possibility that the Chinese can lose

their culture and become the uncivilized outsiders, and that the

uncivilized outsiders have the potential to become Chinese.

Interestingly, after the Song Dynasty, many of China's rulers in

the north were of Inner Asia ethnicities, such as Qidan, Ruzhen,

and Mongols of the Liao, Jin and Yuan Dynasties, the latter ended

up ruling over the entire China. Hence, the

historian John King

Fairbank wrote, "the influence on China of the

great fact of alien conquest under the Liao-Jin-Yuan dynasties is

just beginning to be explored."[67] During

the Qing Dynasty, the rulers of China adopted Confucian philosophy

and Han Chinese institutions to show that the Manchu rulers had

received the Mandate of Heaven to rule China. At the same time,

they also tried to retain their own indigenous culture.[68] Due

to the Manchus' adoption of Han Chinese culture, most Han Chinese

(though not all) did accept the Manchus as the legitimate rulers of

China. Similarly, according to Fudan University historian Yao Dali,

even the supposedly "patriotic" hero Wen Tianxiang of the late Song

and early Yuan period did not believe the Mongol rule to be

illegitimate. In fact, Wen was willing to live under Mongol rule as

long as he was not forced to be a Yuan dynasty official, out of his

loyalty to the Song dynasty. Yao explains that Wen chose to die in

the end because he was forced to become a Yuan official. So, Wen

chose death due to his loyalty to his dynasty, not because he

viewed the Yuan court as a non-Chinese, illegitimate regime and

therefore refused to live under their rule. Yao also says that many

Chinese who were living in the Yuan-Ming transition period also

shared Wen's beliefs of identifying with and putting loyalty

towards one's dynasty above racial/ethnic differences. Many Han

Chinese writers did not celebrate the collapse of the Mongols and

the return of the Han Chinese rule in the form of the Ming dynasty

government at that time. Many Han Chinese actually chose not to

serve in the new Ming court at all due to their loyalty to the

Yuan. Some Han Chinese also committed suicide on behalf of the

Mongols as a proof of their loyalty.[69] We

should note that the founder of the Ming Dynasty, Zhu Yuanzhang,

also indicated that he was happy to be born in the Yuan period and

that the Yuan did legitimately receive the Mandate of Heaven to

rule over China. On a side note, one of his key advisors, Liu Ji,

generally supported the idea that while the Chinese and the

non-Chinese are different, they are actually equal. Liu was

therefore arguing against the idea that the Chinese were and are

superior to the "Yi."[70]

These things show that many times, pre-modern Chinese did view

culture (and sometimes politics) rather than race and ethnicity as

the dividing line between the Chinese and the non-Chinese. In many

cases, the non-Chinese could and did become the Chinese and vice

versa, especially when there was a change in culture.

Modern

reinterpretations

According to the historian Frank

Dik?tter, "The delusive myth of a Chinese antiquity that

abandoned racial standards in favour of a concept of cultural

universalism in which all barbarians could ultimately participate

has understandably attracted some modern scholars. Living in an

unequal and often hostile world, it is tempting to project the

utopian image of a racially harmonious world into a distant and

obscure past."[71]

The politician, historian, and diplomat K. C.

Wu analyzes the origin of the characters for

the Yi, Man, Rong, Di, and Xia peoples and

concludes that the "ancients formed these characters with only one

purpose in mind—to describe the different ways of living each of

these people pursued."[72]Despite

the well-known examples of pejorative exonymic characters (such as

the "dog radical" in Di), he claims there is no hidden racial bias

in the meanings of the characters used to describe these different

peoples, but rather the differences were "in occupation or in

custom, not in race or origin."[73] K.

C. Wu says the modern character 夷 designating

the historical "Yi peoples," composed of the characters for 大 "big

(person)" and 弓 "bow", implies a big person carrying a bow, someone

to perhaps be feared or respected, but not to be

despised.[74] However,

differing from K. C. Wu, the scholar Wu Qichang believes that the

earliest oracle bone

script for yi 夷

was used

interchangeably with shi 尸 "corpse".[75] The

historian John Hill explains that Yi "was used rather

loosely for non-Chinese populations of the east. It carried the

connotation of people ignorant of Chinese culture and, therefore,

'barbarians'."[76]

Christopher I. Beckwith makes the extraordinary claim that the name

"barbarian" should only be used for Greek historical contexts, and

is inapplicable for all other "peoples to whom it has been applied

either historically or in modern times."[77] Beckwith

notes that most specialists in East Asian history, including him,

have translated Chinese exonyms as English "barbarian." He believes that after

academics read his published explanation of the problems, except

for direct quotations of "earlier scholars who use the word, it

should no longer be used as a term by any writer."[78]

The first problem is that, "it is impossible to translate the

word barbarian into Chinese

because the concept does not exist in Chinese," meaning a single

"completely generic" loanword from

Greek barbar-.[79] "Until

the Chinese borrow the word barbarian or one of its

relatives, or make up a new word that explicitly includes the same

basic ideas, they cannot express the idea of the 'barbarian' in

Chinese.".[80] The

usual Standard

Chinesetranslation of English barbarian is yemanren (traditional

Chinese: 野蠻人; simplified

Chinese: 野蛮人; pinyin: ymánrén),

which Beckwith claims, "actually means 'wild man, savage'. That is

very definitely not the same thing as 'barbarian'."[80] Despite

this semantic hypothesis, Chinese-English dictionaries regularly

translate yemanren as "barbarian"

or "barbarians."[81] Beckwith

concedes that the early Chinese "apparently disliked foreigners in

general and looked down on them as having an inferior culture," and

pejoratively wrote some exonyms. However, he purports, "The fact

that the Chinese did not like foreigner Y and

occasionally picked a transcriptional character with negative

meaning (in Chinese) to write the sound of his ethnonym, is

irrelevant."[82]

Beckwith's second problem is with linguists and lexicographers of

Chinese. "If one looks up in a Chinese-English dictionary the two

dozen or so partly generic words used for various foreign peoples

throughout Chinese history, one will find most of them defined in

English as, in effect, 'a kind of barbarian'. Even the works of

well-known lexicographers such as Karlgren do this."[83] Although

Beckwith does not cite any examples, the Swedish

sinologist Bernhard

Karlgren edited two

dictionaries: Analytic Dictionary of Chinese and

Sino-Japanese (1923)

and Grammata

Serica Recensa(1957). Compare Karlgrlen's translations of

the siyi "four

barbarians":

- yi 夷 "barbarian,

foreigner; destroy, raze to the ground," "barbarian (esp. tribes to

the East of ancient China)"[84]

- man 蛮 "barbarians of

the South; barbarian, savage," "Southern barbarian"[85]

- rong 戎 "weapons,

armour; war, warrior; N. pr. of western tribes," "weapon; attack;

war chariot; loan for tribes of the West"[86]

- di 狄 "Northern

Barbarians – "fire-dogs"," "name of a Northern tribe; low

servant"[87]

The Sino-Tibetan

Etymological Dictionary and Thesaurus Project

includes Karlgren's GSR definitions.

Searching the STEDT

Database finds various "a kind of" definitions

for plant and animal names (e.g., you 狖 "a kind of

monkey,"[88] but

not one "a kind of barbarian" definition. Besides faulting Chinese

for lacking a general "barbarian" term, Beckwith also faults

English, which "has no words for the many foreign peoples referred

to by one or another Classical Chinese word, such as

胡 hú,

夷 yí,

蠻 mán, and so

on."[89]

The third problem involves Tang

Dynasty usages of fan "foreigner"

and lu "prisoner", neither

of which meant "barbarian." Beckwith says Tang texts

used fan 番 or 蕃 "foreigner"

(see shengfan and shufan above)

as "perhaps the only true generic at any time in Chinese

literature, was practically the opposite of the

word barbarian. It meant simply 'foreign,

foreigner' without any pejorative meaning."[90] In

modern usage, fan 番 means "foreigner;

barbarian; aborigine". The linguist Robert Ramsey illustrates the

pejorative connotations of fan.

The word "Fn" was formerly used

by the Chinese almost innocently in the sense of 'aborigines' to

refer to ethnic groups in South China, and Mao Zedong himself once

used it in 1938 in a speech advocating equal rights for the various

minority peoples. But that term has now been so systematically

purged from the language that it is not to be found (at least in

that meaning) even in large dictionaries, and all references to

Mao's 1938 speech have excised the offending word and replaced it

with a more elaborate locution, "Yao, Yi, and Yu."[91]

The Tang Dynasty Chinese also had a derogatory term for

foreigners, lu (traditional

Chinese: 虜; simplified

Chinese: 虏; pinyin: l)

"prisoner, slave, captive". Beckwith says it means something like

"those miscreants who should be locked up," therefore, "The word

does not even mean 'foreigner' at all, let alone

'barbarian'."[92]

Christopher I. Beckwith's 2009 "The Barbarians" epilogue provides

many references, but overlooks H. G. Creel's 1970 "The Barbarians"

chapter. Creel descriptively wrote, "Who, in fact, were the

barbarians? The Chinese have no single term for them. But they were

all the non-Chinese, just as for the Greeks the barbarians were all

the non-Greeks."[93] Beckwith

prescriptively wrote, "The Chinese, however, have still not yet

borrowed Greek barbar-. There is also no single native

Chinese word for 'foreigner', no matter how pejorative," which

meets his strict definition of "barbarian.".[80]

Allusions in poetry

Conventionally Chinese poets did not directly criticize the ruling

emperor or even the current dynasty: such poetic practice was both

an aesthetic principle as well as a practical method of prudently

avoiding punishment for treason, or lèse-majesté.[94] Although

socio-political criticism was an important aspect of Chinese

poetry, generally if it involved the reigning monarch and the

current dynasty it was done indirectly and with subtle

circumspection: it was "a custom almost universally followed by

Chinese poets to refer to their own dynasty and to the reigns of

emperors contemporary with them by indirect means and in

complimentary terms."[95] Lack

of success in war was potentially a capital offense for a general,

and considered unmentionable in direct regard to the emperor. Thus

poetic references or allusions to a current armed conflict between

the Chinese empire and an external nation would be done through the

substitution in time to a former dynasty; for example, reference to

the Han dynasty and its leaders by Tang poets; and the real ethnic

identity of the opposing force masked by substitution; for example,

the Tang dynasty poems about battling

the Xiongnu, although

clearly anachronistic several centuries, by then. Thus, although

the poets' comments about the nature of the situation might be

accurate enough, the actual identity of the ethnically-named

opponents can generally be relied upon to be different than that

named. In English translation, further confusion regarding specific

historic identity of people or events referred or alluded to

results from the translation process; for example, in the case

of Chen Tao's

28-character verse entitled "隴西行",

one of the Three

Hundred Tang Poems which has often been

translated into English.

Barbarian puppet drinking

game

In the Tang

Dynasty houses of pleasure, where drinking

games were common, small puppets in the aspect of Westerners, in a

ridiculous state of drunkenness, were used in one popular

permutation of the drinking game; so, in the form of blue-eyed,

pointy nosed, and peak-capped barbarians, these puppets were

manipulated in such a way as to occasionally fall down: then,

whichever guest to whom the puppet pointed after falling was then

obliged by honor to empty his cup of Chinese

wine.[96]

Japanese culture

When Europeans came to Japan, they were

called nanban (南蛮?),

literally Barbarians from the South, because

the Portuguese ships

appeared to sail from the South. The Dutch, who arrived

later, were also called either nanban or km (紅毛?),

literally meaning "Red Hair."

American cultures

In Mesoamerica the Aztec civilization

used the word "Chichimeca" to

denominate a group of nomadic hunter-gatherer tribes that lived on

the outskirts of the Triple

Alliance's Empire, in the north of Modern Mexico, and whom the

Aztec people saw as primitive and uncivilized. One of the meanings

attributed to the word "Chichimeca" is "dog people".

The Incas of

South America used the term "puruma auca" for all peoples living

outside the rule of their empire (see Promaucaes).

The British and later, the white settlers of

the United

States referred to Native Americans as

"savages."

Barbarian

mercenaries

The entry of "barbarians" into mercenary service

in a metropole repeatedly occurs in history as a standard way in

which peripheral peoples from and beyond frontier regions

relate to "civilised" imperial powers as part of a (semi-)foreign

militarised proletariat.[97] Examples

include:

Early Modern

period

Italians in the Renaissance often

called anyone who lived outside of their country a

barbarian[citation

needed].

Spanish sea captain Francisco de

Cuellar who sailed with

the Spanish

Armada in 1588 used the term 'savage'

('salvaje') to describe the Irish

people.[106]

Marxist use of

"Barbarism"

In her "Junius Pamphlet" of

1916, strongly denouncing the then

raging First World

War, Rosa

Luxemburgwrote: Bourgeois society stands at the crossroads,

either transition to Socialism or regression into

Barbarism.[107]

Luxemburg attributed it to Friedrich

Engels, though – as shown by Michael

L?wy – Engels had not used the term

"Barbarism" but a less resounding

formulation: If

the whole of modern society is not to perish, a revolution in the

mode of production and distribution must take

place [108]

Luxemburg went on to explain what she meant by "Regression into

Barbarism": "A look around us at this moment [i.e., 1916 Europe]

shows what the regression of bourgeois society into Barbarism

means. This World War is a regression into Barbarism. The triumph

of Imperialism leads to the annihilation of civilization. At first,

this happens sporadically for the duration of a modern war, but

then when the period of unlimited wars begins it progresses toward

its inevitable consequences. Today, we face the choice exactly as

Friedrich Engels foresaw it a generation ago: either the triumph of

Imperialism and the collapse of all civilization as in ancient

Rome, depopulation, desolation, degeneration – a great cemetery. Or

the victory of Socialism, that means the conscious active struggle

of the International Proletariat against Imperialism and its method

of war."

"Socialism or Barbarism" became, and remains, an often quoted and

influential concept in Marxist literature.

"Barbarism" is variously interpreted as meaning either a

technologically advanced but extremely exploitative and oppressive

society (e.g. a victory and world domination

by Nazi

Germany and its Fascist allies); a collapse of

technological civilization due to Capitalism causing

a Nuclear

War or ecological

disaster; or the one form of barbarism bringing on the

other.

The Internationalist

Communist Tendency considers "Socialism or

Barbarism" to be a variant of the earlier "Liberty

or Death", used by revolutionaries of different stripes since

the late 18th century [109]

Modern popular

culture

Modern popular culture contains such fantasy barbarians

as Conan the

Barbarian.[110] In

such fantasy, the negative connotations traditionally associated

with "Barbarian" are often inverted. For example, "The

Phoenix on the Sword" (1932), the first

of Robert E.

Howard's "Conan" series, is set soon after the "Barbarian"

protagonist had forcibly seized the turbulent kingdom

of Aquilonia from

King Numedides, whom he strangled upon his throne. The story is

clearly slanted to imply that the kingdom greatly benefited by

power passing from a decadent and tyrannical hereditary monarch to

a strong and vigorous Barbarian usurper.

![]()